In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown will look at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

War is an ugly business. While many books focus on the gallantry and bravery, the triumph and victory, that certainly doesn’t represent all that war is. There is the dehumanizing nature of military service; becoming a cog in the machine. Not to mention the deprivation, pain, and suffering that one endures on the front lines. Anyone who has been in the military is familiar with gallows humor, and has seen people make jokes about things that under normal circumstances wouldn’t be funny. Human beings seem programmed to defiantly laugh at the worst life can throw at them, and the adventures of Bill, the Galactic Hero will certainly make you laugh.

Sometimes when I write these columns, I feel like the character, Colonel Freeleigh, in Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine—the one the kids call the “Time Machine,” because his stories take them back to a different time. But I like to talk about my younger days, and looking at the time when a work was produced gives it a context. You can’t ignore the fact that Bill, the Galactic Hero was written in the early 1960s, at a time when U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was growing rapidly, with the number of troops increasing significantly every year. The Gulf of Tonkin incident was used as a pretext by Congress to increase US involvement, even though participants in the decision-making process admitted that accounts of the incident had been inflated. The military focused heavily on questionable statistics, including enemy body counts, to measure the effectiveness of their actions. And as the military effort grew, so did an anti-war movement that was not willing to buy the argument being offered by the establishment. In fact, there are those who argue that the Viet Cong’s Tet Offensive in 1968 was not successful militarily, but succeeded instead in the court of public opinion, discrediting the establishment arguments and repudiating military claims of an enemy on the run. This was not the finest hour of the U.S. military.

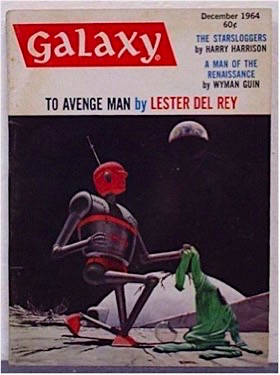

During the 1960s, a period when U.S. society was polarized on many issues, I was exposed to different political viewpoints right in my own home. My father, a pocket protector-wearing aerospace engineer and Army Reserve officer, was a staunch Republican. My mother, who had seen the New Deal save her family farm, and bring electricity to her home, was a staunch Democrat. I saw that same split in the two science fiction magazines my dad subscribed to. Analog, edited by John W. Campbell, was deeply conservative, in some ways even reactionary in its political viewpoint. The worldview of Analog seemed to fit my father’s viewpoint to a T. Galaxy, on the other hand, was at the time edited by Frederik Pohl and presented a whole different world—focused less on hard science, more experimental, and featuring more humor and satire. The mere presence of Galaxy in the house told me that my father was not quite as rigid in his thinking as he appeared. And growing up with parents of opposing political opinions, and reading both of these magazines, I realized that there were different ways of viewing the world.

Harry Harrison, born in Connecticut in 1925, lived a broad and varied life. Like many of his generation, he did military service in World War II, serving in the Army Air Corps. He was a technician, working on bombsights and aiming devices, and also served as a military policeman. He developed a deep dislike for the military and bureaucracy during that service, a dislike that colored his work throughout his life. His start in genre fiction actually came in the world of comic books, as an illustrator and later a writer for EC comics and as a writer for the Flash Gordon newspaper strips. When the comic book industry fell on hard times in the ‘50s, however, he turned to science fiction writing. He was originally part of John Campbell’s stable of writers at Astounding Science Fiction. His first major work, the Deathworld trilogy, got its start in installments in Astounding. He also began his long series of stories about the con man James Bolivar DiGriz, known as “The Stainless Steel Rat,” a series that demonstrated his distrust of bureaucracies and governmental institutions. While he respected John Campbell, he chafed at the rigid restrictions placed on writers at Astounding, and his work began to appear elsewhere.

It was in the December 1964 edition of Galaxy that I first encountered Bill in “The Starsloggers,” a “short novel” that was later expanded into the novel Bill, the Galactic Hero. The cover story of that issue, “To Avenge Man,” by Lester Del Rey, is another story that stuck with me because of its bleak premise—a bleakness that you wouldn’t have encountered in Analog. And there was a bleakness in “The Starsloggers,” as well as a mistrust of all things military, which I found quite different than anything I had encountered before.

It was in the December 1964 edition of Galaxy that I first encountered Bill in “The Starsloggers,” a “short novel” that was later expanded into the novel Bill, the Galactic Hero. The cover story of that issue, “To Avenge Man,” by Lester Del Rey, is another story that stuck with me because of its bleak premise—a bleakness that you wouldn’t have encountered in Analog. And there was a bleakness in “The Starsloggers,” as well as a mistrust of all things military, which I found quite different than anything I had encountered before.

The book Bill, the Galactic Hero begins with young Bill, an inhabitant of the backwater world of Phigerinadon II, in a very contented frame of mind. He is helping his mother by plowing the fields, and is happy to do so, but he also knows that he has a brighter future ahead once he completes his correspondence course for the position of Technical Fertilizer Operator. His fantasies about a local girl are interrupted, though, by the arrival of a recruiting sergeant. The red-coated sergeant uses tactics that were old when the British Army used them in the 19th Century, but augmented by the most modern psychological theories and mind-control devices. Soon Bill finds himself shipped off to boot camp, where he finds himself a victim of the purposeful cruelty of his drill instructor, Chief Petty Officer Deathwish Drang, a man so enamored of his vicious image that he has had fangs implanted to replace some of his teeth. The recruits are being trained to engage in total war with the Chingers, alien lizard-men whose very existence stands in the way of humanity’s imperial aims. The recruits are constantly reminded by lurid propaganda of the evil nature of the Chingers. Bill and the widely-varied recruits he serves with do their best to survive until they, and the entire staff of their camp, are sent off to the front lines.

Bill soon finds himself pressed into naval service, under the instruction of Fuse Tender Sixth Class Tembo, a kindly but eccentric religious man. Bill learns the brutal trade of fuse replacement, a mindless, dangerous, but necessary task during combat. He becomes aware of a suspicious member of the crew, and thwarts his efforts. When the ship is damaged in combat, and Tembo is killed, Bill finds himself stumbling into heroism, almost accidently destroying an enemy ship and turning the tide of the battle. He also loses his right arm in the battle, and finds that the surgeons, in their haste, have replaced it with the left arm of Tembo. (This causes some different interpretations in artistic renditions of Bill, some portraying him with the two arms both on the left side, with others showing the new left arm affixed to his right shoulder.)

Bill is then shipped off to the capitol planet to be decorated for bravery. He finds the reality of that planet-spanning city and its royalty somewhat less attractive than its reputation, and soon winds up lost, robbed, and accused of being a deserter. Whenever facts and bureaucracy clash, he notices that it is the bureaucracy that prevails. In his adventures moving ever down the ladder of society, he finds his original training as a fertilizer operator becoming unexpectedly useful, until finally he is captured and put on trial. Cleared from these charges, he bounces from the frying pan into the fire, sent to fight in the jungles of the planet Veneria, a planet whose jungles bear no small resemblance to the jungles of Vietnam. And in the end, Bill finds that his career has brought him full circle, though he’s now a very different person from the boy who contentedly plowed his mother’s fields.

A plot summary can’t possibly capture the absurdity and the humor of Bill’s adventures, nor can it capture the many jokes the reader will encounter along the way (and summarizing those jokes would tend to spoil them). Harrison’s version of faster-than-light travel, for example, is not only absurd in and of itself, it illustrates the absurdity of so many other methods described in science fiction. And through it all, his many observations on the true and dehumanizing nature of war are direct and to the point. Anyone who has served in the military will recognize example after example of things that echo their own service. If you weren’t laughing so much, the book could easily make you cry.

Harry Harrison’s career in subsequent years was prolific and wide-ranging. In addition to appearing in Astounding/Analog and Galaxy, his short works appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction, If and Vertex. His novel Make Room! Make Room! was later adapted into the movie Soylent Green. His books included further adventures of the Stainless Steel Rat, a prehistoric alternate history series that started with the novel West of Eden, an alternate history Civil War trilogy starting with Stars and Stripes Forever, and humorous novels like The Technicolor Time Machine, and A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! In the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the help of collaborators, Bill the Galactic Hero returned in a series of humorous novels. Harrison’s works were noted for their thoughtfulness, their humor, and his skill portraying action and adventure. Until his death in 2012, he was an influential presence in the science fiction community, and a staunch representative of its more liberal wing. One of my great regrets as a member of SF fandom is that, in all the conventions I attended, I never had the opportunity to meet him.

Harry Harrison’s career in subsequent years was prolific and wide-ranging. In addition to appearing in Astounding/Analog and Galaxy, his short works appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction, If and Vertex. His novel Make Room! Make Room! was later adapted into the movie Soylent Green. His books included further adventures of the Stainless Steel Rat, a prehistoric alternate history series that started with the novel West of Eden, an alternate history Civil War trilogy starting with Stars and Stripes Forever, and humorous novels like The Technicolor Time Machine, and A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! In the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the help of collaborators, Bill the Galactic Hero returned in a series of humorous novels. Harrison’s works were noted for their thoughtfulness, their humor, and his skill portraying action and adventure. Until his death in 2012, he was an influential presence in the science fiction community, and a staunch representative of its more liberal wing. One of my great regrets as a member of SF fandom is that, in all the conventions I attended, I never had the opportunity to meet him.

What struck me about rereading Bill, the Galactic Hero for this column was how different it felt the second time around. When I first read it, it appeared as slapstick to me, rather dark in tone, but slapstick nonetheless. Reading it now, after long exposure to the military and with a better knowledge of history, I was struck by how much truth was mixed into the absurdity. The sometimes pointless campaigns, mindless bureaucracy, loss of individuality, wastefulness and suffering in warfare all resonated in a way that was lost on me in my youth. There are plenty of books that look at the adventure, bravery and glory of war. But we also need books like Bill, the Galactic Hero to remind us of the aspects of war that we might otherwise ignore. The humor makes it easy to read, but there is a strong dose of medicine mixed in with that sugar, medicine that we all need to remind us of the very real horrors of war.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy.

I found this one an entertaining dark comedy but the (mostly farmed-out) sequels were… regrettable. The Harrison I like best is The Technicolor Time Machine.

Another book in a similar vein to Bill, the Galactic Hero is Bob Shaw’s Who Goes Here?, in which our protagonist (the memorably-named Warren Peace) joins the Space Legion in order to forget. Forgetting, in the 24th century, involves electronic memory removal, so Warren must try to relearn who he is while staying alive on the front line of an absurd war. (This one also got an inferior sequel in the 90’s.)

Another book that I read when I was probably too young for it, first encountered as I was trawling the SF section of the local public library.

I also have a lot of fondness for Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers, his send-up of Hamiltonion space opera excess.

Huh, I always thought Star Smashers was more of a Doc Smith parody myself.

I liked Bill the Galactic Hero but it always felt like a fixup novel to me (I don’t remember it well enough to know if that was the case).

The ending was always horrifying to me, knowing that Bill not only doesn’t remember, but that he doesn’t have any mercy left. Ugh!

Yes, Star Smashers could’ve been Smith — I’ve read more Hamilton than Smith myself, so that’s where my mind went. (And, to be clear, I didn’t read either Hamilton or Smith until after reading Star Smashers, at which point a whole bunch of things suddenly fell into place.)

I got a strong feel of the Skylark series from parts of Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers, however, I suspect that the greatest parody of Doc Smith’s work is Randall Garrett’s “Backstage Lensman”.

@3 Bill, the Galactic Hero wasn’t a fix-up, which I would define as related stories stitched together, but it certainly was an expansion of a shorter work.

@5 Randall Garrett. Now, that’s a name I’ve not heard in a long, long time. And, having been reminded of that name, I think the adventures of Lord Darcy would make an excellent topic for a future column.

Thanks for the review. I read Bill as a teenager and I remember enjoying it very much, especially his description of the FTL drive. My favorite stories are his The Stainless Steel Rat books. I’ve read my hardcover copy of The Stainless Steel Rat For President so many times that it is falling apart.

@7 You’re welcome. I wouldn’t mind revisiting the Stainless Steel Rat again. So many books, so little time.

I can’t remember how long ago it was that I read any Harry Harrison. He was one of my favourite space opera authors, along with E Doc Smith; I read the whole Lensmen series whilst on holiday many years ago. Stainless Steel Rat creased me up but perhaps, now that I am more mature, I should read it again paying more attention to the sub text. I never got round to reading Bill the Galactic Hero but I have a feeling I will shortly be downloading the series to my Kindle. Speaking of space heroes, could I just lead a cheer for space heroines. in particular Torin Kerr in Tanya Huff’s Confederation Series and Heris in Elizabeth Moon’s The Serrano Legacy True space opera.

Bill, The Galactic Hero has been a top favorite of mine since I first picked it up as a kid collecting Ace Doubles at the Used Book Store on 9th Street in Washington, DC. Getting the nod to assist the Cover Art for the (sometimes hapless) sequels was an unexpected treat… working out JUST how to get Tembo’s arm onto Bil’s Body (two “L”s are for Officers only) so he could shake hands with himself was a head-scratcher, but ultimately successful. Coming up with the Party Polaroid Photo approach to the Interion Illustrations of these sequels made me feel clever and saved me a lot of work: if the books had been pure Harrison, I’d have gone for the Standard Full Page Art. That said, I felt the Polaroid Photo approach “fit in” with the Sensibility of Bill.

I got to meet Harry Harrison at Byron Preiss’s office during the run of these Extra-Bill books and chastized him for abruptly shutting down the Robot Slaves arc by dropping an inferion ERB lampoon right as the Robot Theme was developing a life of its own. Harry didn’t hit me, exactly, but might have if we’d been alone :) There was definite Pleasure in meeting and arguing with Harrison from my position of strength: since I really had to absorb the writing to do the art, Harry couldn’t sneak under what was written with any defense, except his Final Word: “You Artists: Always Complaining and Knowing Nothing.” Harry’s wife was in the office at the same time (as was Byron) and she adeptly poured cream on the turbulized waters. Her Masterful tugging on Harry’s strings gave one a clue to just what a topsey-turvey life the two of them had together… she finally nailed her supremacy in the cross-talk by letting us all know that SHE was the Driver, that Harry was the Passenger (meaning that Harry couldn’t or wouldn’t learn to drive, but meaning so much more). It was a delight to see Harry reigned in by such a practiced hand… he didn’t mind it a bit.

My only ever Art Argument with Byron (and then, after the fact with Harry) was on the cover for Planet of the Robot Slaves: *I* believed it’d been a lot funnier if Bill had been weilding a Sledge Hammer, insted of the broken sword… ah well :)

The cherry on the top of all this: I did get to do a cover drawing for the Actual Novel, but, beg as I would, no interior illustrations.

I can’t talk about these Bill the Galactic Hero Sequel Covers without putting Mr Steve Fastner’s name forward: Steve took my penciled offerings and smacked them into Full Life with his painting skills. (and I’ll also note that once Mark Pacella took over the cover drawings, the printed cover work, again laid down by Steve Fastner, maintained that Full Bil Fun!

I’ll end with another favorite quote from the original novel: “Bill was born stupid, but was learning”

@10 Thanks for the insights!

At the very first Campbell Award conference, organized by Leon Stover, at IIT in 1973, I got to meet Harry Harrison.

Anyhow, I like a lot of Mr Harrison’s stories. This was in an era when many sf/f writers were pretty gung ho pro-military, and Harry’s rather cynical anti-militarism was a breath of fresh air

The book felt like a necessary corrective to Starship Troopers; the military life it portrayed jibed perfectly with a relative’s Foreign Legion reminiscences….

On the other hand, a curry pizza seemed like something that could be well worth the eating, done right—but then again, what in Bill’s universe was ever done right?

a curry pizza seemed like something that could be well worth the eating, done right

They exist in our universe! https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/recipes/1126635/chicken-tikka-pizza

WW2 had the effect of exposing a large part of the population to the absurdity of military bureaucracy, including a lot of men who went on to become comic writers. From that we get surreal humour like “Bill the Galactic Hero” and also, in the UK, people like Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers; the Pythons were all just too young to be conscripted, but it was definitely in the air.

I’ve long thought that the best way to put people off war isn’t by showing them how awful it is. That just makes it sound grand and dramatic and important. (“It is well war is so terrible, or else we should grow fond of it” – no, it’s because war is so terrible that we grow fond of it.) The best way to put them off is to show them how ludicrous and frustrating it is. Platoon isn’t an anti-war film, but Generation Kill is an anti-war series.

@14/ajay: I doesn’t sound grand and dramatic and important if you show people the whole range of injuries they could get. There’s a lot there that’s terrible and ludicrous at the same time.